Weak accountability

The November 19, 2013, interview of officer Ruth Castelli took place at IPRA's West Town office, a little more than six miles from where she shot and killed Jamaal Moore. IPRA's office sits on the fourth floor of a redbrick building, where tall windows are framed in forest green.

The interview began around 10 AM, and Castelli's team of lawyers and union reps outnumbered the investigators present to tackle her case—one IPRA investigator's questions were scrutinized by Castelli, her lawyer, and her FOP field rep, Kriston Kato.

Castelli began the interview by noting that, per Kato's advice, "I am not making this statement voluntarily but under duress and am only making this statement at this time because I know that I could lose my job if I refuse."

Castelli's entourage and her disclaimer point to one way the FOP does more than shape public perception of a shooting; the union also has the power to influence follow-up investigations via its contract

with CPD.

In these instances, a strong union contract comes up against IPRA's weak and slow-moving accountability system, in which investigations take an average of 328 days to resolve.

The current agreement between Lodge 7 and the city runs through June 30, 2017, and lays out a wide range of contractual protections, from when and how an officer can be interviewed (during daylight hours, while on duty) to a provision making the results of a polygraph inadmissible in cases brought before the police board.

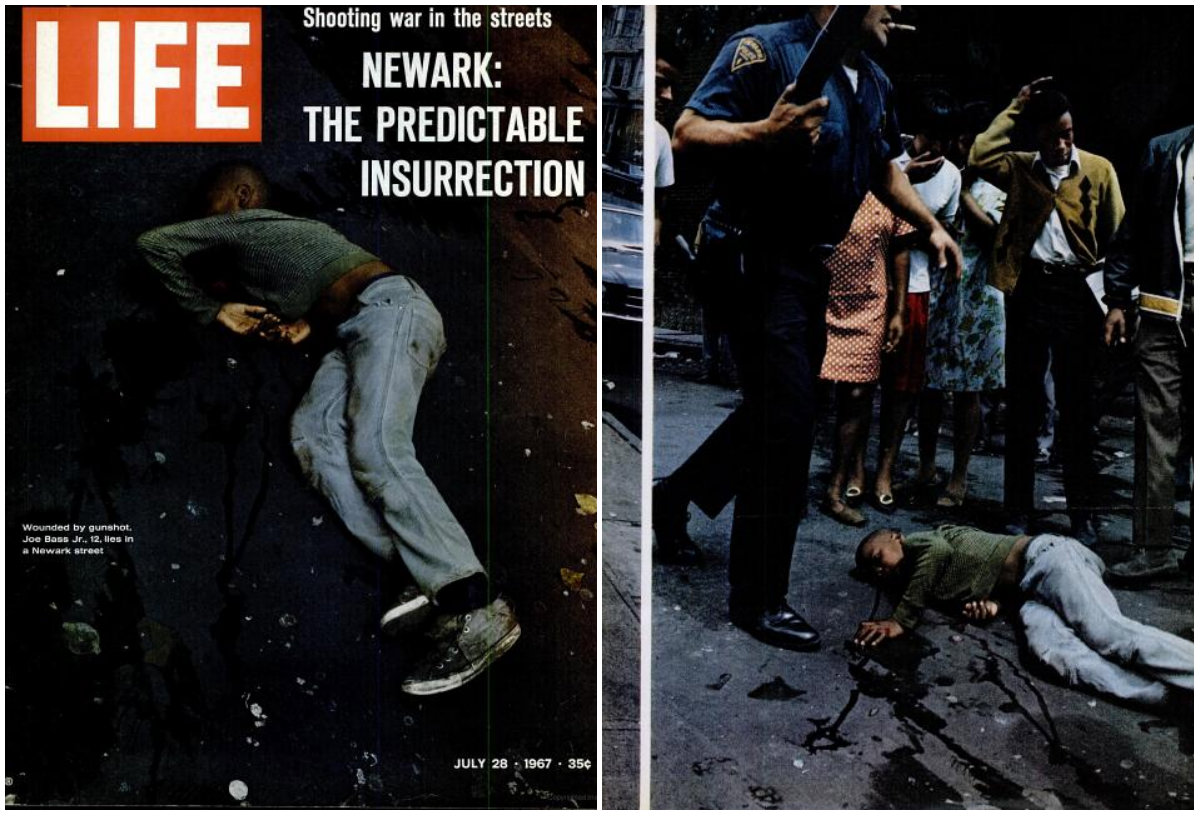

"The power balance has changed, because now, unlike the 60s, they have these various provisions in their contracts which provide special protections and special privileges," says Walker, the police-accountability expert.

As stipulated by the union contract, a police officer accused of misconduct has up to 48 hours before he or she is interviewed by IPRA, though this shrinks to two hours in the case of a shooting, with allowance for an individual officer's extenuating circumstances. (Strikingly, Castelli's IPRA interview took place nearly a year after she shot and killed Moore.) From there, IPRA must provide the names of the primary and secondary investigators, as well as those of anyone else who will be in the room. A maximum of two members of IPRA or the Internal Affairs Department can be present in an interview at a time.

Kato, a former violent-crimes detective on the west side, was himself accused of misconduct during his time on the force. In 1991 the Readerreported on allegations that Kato, who is Asian-American, had beaten false confessions out of people, many of whom were African-American.

Any influence Kato may have had on Castelli's interrogation is hard to pin down. Though the FOP contract stipulates that a union rep can advise officers during the interview, there are no statements from Kato recorded in the Moore case transcripts.

The IPRA investigator, Kymberly Reynolds, was herself a police officer with the LAPD from 1989 to 1991. Since 2010 she has not disciplined an officer listed in any of the 159 complaints she's investigated, according to the Citizens Police Data Project.

Three months after Reynolds interviewed Castelli, IPRA cleared her of any wrongdoing in Moore's death, finding that she acted in accordance with the department's use-of-force policy. According to department records, Castelli is still employed by CPD.

In a statement, IPRA said, "We are aware that the union contract governs how we interact with officers. We're examining the contract to see if there might be changes that can be made in the future."

The Laquan McDonald case

On the evening of October 20, 2014, police officers received a call that a young man was trying to break into cars in Archer Heights, and that he was armed with a knife. Before the night was out, 17-year-old Laquan McDonald would be dead, shot 16 times by officer Jason Van Dyke.

As in so many other cases, the media machine justifying McDonald's death shifted into full gear, starting with the arrival of Camden on the scene.

Talking to the Tribune, Camden painted the incident in lurid detail: "He's got a 100-yard stare. He's staring blankly. [He] walked up to a car and stabbed the tire of the car and kept walking."

From there, Camden claimed that McDonald "lunged" at police and was then shot in the chest. The officers on the scene, he said, were forced to defend themselves. "You obviously aren't going to sit down and have a cup of coffee with [him]," Camden told CBS 2.

News media reported the case as Camden described it. Chicago police had no choice but to shoot McDonald, NBC Chicago said. Its reporter on the scene repeated the FOP's claims, citing the union as a police source and saying that, though IPRA had launched an investigation, "police say this was a clear-cut case of self-defense." Reports from the Tribune, ABC 7, andCBS 2 echoed that conclusion.

What really happened that night is now evident from the release of autopsy reports and a grainy but painfully clear dashcam video. As McDonald walked away unsteadily from the line of police vehicles, he was shot again and again by Van Dyke. The officer continued to shoot McDonald even after the 17-year-old fell to the ground.

Officials eager to distance themselves from the FOP's initial statements began backtracking the day after the video's November 24 release. Camdentold the Washington Post that his statement about McDonald being a "very serious" threat to the officers wasn't firsthand or even secondhand information. In fact, he said, "I have no idea where it came from."

“[Camden]’s standing up there representing an official body; the public is listening to him represent the police organization, even though it’s the union. The police department and the city administration should be objecting to that; if they’re not, then they’re complicit.”

—RETIRED LAPD DEPUTY CHIEF STEPHEN DOWNING

"I never talked to the officer, period," Camden told the Post. "It was told to me after it was told to somebody else who was told by another person, and this was two hours after the incident . . . hearsay is basically what I'm putting out at that point."

Likewise, then-police chief McCarthy walked back his comments on the shooting, telling NBC Chicago that the initial press release was wrong. He took responsibility for the error— "I guess that's my fault," he said—even though the first media comments had come from Camden.

Indeed, the roughly 3,000 pages of e-mails subsequently released from the mayor's office show a battle to separate the public image of the police department from that of the FOP.

An exchange between John Holden, public affairs director for the city's Law Department, and Shannon Braymaier, deputy director of communications for the mayor's office, regarding the wording in an NBC 5 story about the e-mail release, notes that the station's reference to "the Chicago Police Department's story" about what happened the night McDonald was killed was, in fact, the FOP's story.

"They amended the online story which clarifies the subject line issue, but leaves in the reference to the Chicago Police Department's story. I have told Don [Moseley, the well-respected NBC producer] twice that it was not the 'Chicago Police Department's story' but rather the FOP's. I will continue to monitor," Holden wrote.

"This mistake is the crux of their entire story," Breymaier replied. "This is a completely unnecessary self-inflicted wound that should and could have been easily avoided."

The e-mails also include a letter from McDonald's lawyer, Jeffrey Neslund, spelling out how the city was culpable in letting Camden spread false information. "There must . . . be accountability for the City and the Department's role in allowing false information to be disseminated to the media via the FOP in an attempt to win public approval and falsely characterize the fatal shooting as 'justified,' " Neslund wrote in an e-mail dated March 6, 2015. "Here, within an hour of the shooting, the FOP spokesman gave a statement to the press describing the circumstances surrounding the shooting which contained misrepresentations, misleading information and outright falsehoods."

Downing, the former LAPD deputy chief, also places blame on the CPD and the city for allowing Camden to disseminate false information from a crime scene. "I'd throw his ass in jail in a minute," he said. "That's gotta be the best definition of interfering with an investigation. He's standing up there representing an official body; the public is listening to him represent the police organization, even though it's the union. The police department and the city administration should be objecting to that; if they're not, then they're complicit."

Dominoes of reform

Since the Laquan McDonald shooting, Camden has been noticeably silent; just one of nine police shootings since then—that of Martice Milliner, who was fatally shot in Chatham—featured comments from the FOP rep. An eyewitness interviewed by the Tribune disputed the circumstances of Milliner's killing as laid out by Camden.

Camden attributes his new low profile to the FOP. "I don't respond to shootings anymore unless the union specifically calls me," he says. "It's just the administration policy at this point in time." Dean Angelo, the current Lodge 7 president, told the Tribune in November that the decision was made months after the McDonald shooting and was unrelated. But after a recent panel on police transparency, Angelo told City Bureau and theReader that allegations of Camden making false statements at the scene of police shootings were "concerning," and suggested that Camden should have never given such statements in the first place.

"That's why you don't see Pat Camden out anymore," he said. "I'm the spokesman for the union now. The department makes the statements on the scene now, as it should have always been." He confirmed that Camden is still employed by the union as a media liaison.

Media commentary, meanwhile, has largely turned against the entire policing structure in Chicago, taking the mayor's office, CPD, IPRA, and the FOP to task. A November 27, 2015, editorial by the Tribune, which endorsed Rahm Emanuel in both 2011 and 2015, led with "the more we learn the worse it gets." The Sun-Times, which also endorsed Emanuel both times,called for McCarthy's resignation.

The mayor has responded with a flurry of new measures: extending the pilot body-camera program, creating a task force to review police misconduct, outfitting more officers with Tasers, and appointing a new IPRA chief to overhaul the agency.

CPD is responding too, in part by changing how police deal with the media. The department is developing a formal policy on the distribution of information after a police shooting, says CPD rep Guglielmi.

The policy will be based on others around the country, Guglielmi says, but he declined to give any additional information.

And on December 16, almost three years to the day of Moore's death, the U.S. Department of Justice began a probe into CPD. The civil "pattern or practice" investigation will look into whether the Laquan McDonald case was a paradigm of misconduct and civil rights violations.

The probe could result in a federal consent decree, which would give the DOJ temporary oversight of the police department. Changes mandated by the consent decree could even come head-to-head with aspects of the city's union contract, as has happened in Seattle and Cleveland, both of which have police departments under federal oversight.

![The tenures of Chicago Police superintendents since 1960. [City Bureau/Andrew Fan]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56cfdde2c2ea51668ffa109d/1470002822935-IX0L0LVRX0VLJFL4C545/image-asset.jpeg)

![Do Police Have More Rights Than Juveniles? [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56cfdde2c2ea51668ffa109d/1470002411701-VUF1U49VI9GZPEGJJP1H/Screen+Shot+2016-07-31+at+4.59.51+PM.png)