BY: DARRYL HOLLIDAY

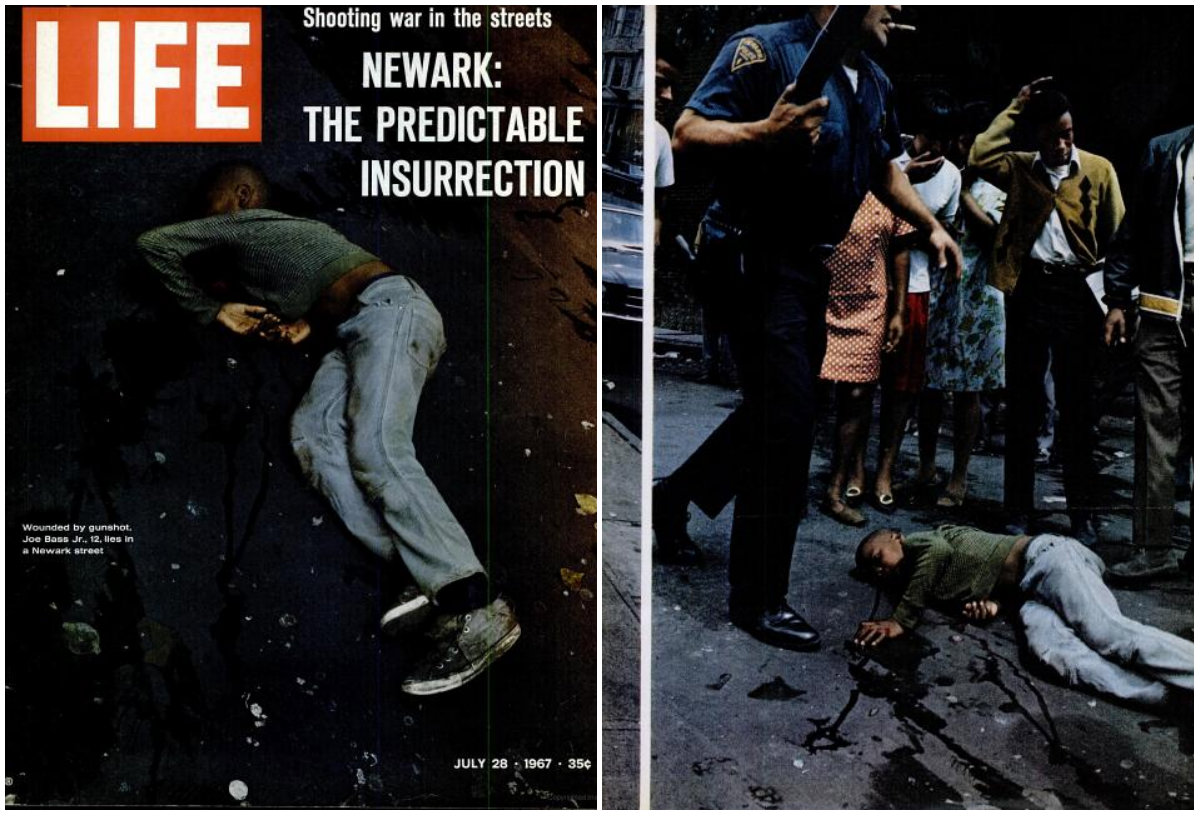

One year ago today, a scathing report on the state of the Chicago Police Department was released to the public. Among its many explosive findings, the mayor-appointed Police Accountability Task Force found that “CPD’s own data gives validity to the widely held belief the police have no regard for the sanctity of life when it comes to people of color.”

A week after that, Mayor Rahm Emanuel proclaimed that the city was placing a “down payment” on police reform—committing to 25 of the 126 recommendations made in the report—but, according to members of the task force, legal experts, and other local leaders, that payment has not been made in full.

Of the 25 items Emanuel promised to implement “immediately,” nearly half have been put into play, according to an analysis by City Bureau, a nonprofit journalism group. Some critical changes have shown success, but many have been stymied.

The city acknowledges the completion rate doesn’t look great, but emphasizes that it is committed to a sustained effort. “I think you could look at this and say ‘barely half are implemented,’ but what you want to look at is that the from the very beginning, [we’ve been] committed to engaging on these reforms and making them happen,” Deputy Mayor Andrea Zopp said. “If you look at the body of work, a significant number are implemented, the majority of the rest are underway and there’s been a clear commitment to get them done.”

Below is a synopsis of where the city has made substantial progress, where it has failed, and where it is stuck in limbo, collected from City Bureau and Invisible Institute’s “One Year Later” Tracker, an annotated version of the mayor’s 25 proposed reforms that is open to public comment.

Now in Play

Progress within the department’s Crisis Intervention Team training (to help officers approach mental health situations) is “encouraging,” according to Alexa James, the executive director of National Association on Mental Illness and a former Police Accountability Task Force member.

“They’re taking the [Department of Justice] report seriously,” James says. “People may be frustrated because training has slowed down, but it’s because they’re not doing a Band-Aid fix just to get numbers up. They’re building a foundational team.”

That team includes a new leader, 16-year CPD veteran Lt. Antoinette Ursitti, more sergeants, more community partners, and more officers engaged with the program on a volunteer basis. But when it comes to the raw numbers promised by the mayor in April 2016, James says the department’s 30 percent certification goal is unlikely to be met by the end of 2017.

Three other items that are either implemented or underway include expanded use of body cameras, the development of an Early Intervention System to find and retrain officers that are likely to commit misconduct, and the recording of all Bureau of Internal Affairs interviews, according to Karen Sheley of the American Civil Liberties Union and the CPD’s March 2017 “Next Steps for Reform” report.

Likewise, Chicago Survivors executive director Susan Johnson says that “things are going extremely well with CPD” when it comes to providing relief for Chicago families affected by homicide through the nonprofit’s support and training.

“We prize our relationship with the CPD,” she adds. “I’d call it a good and complex relationship. I think we’ve been making some good progress.”

Stalled or Unknown

According to two members of the Police Accountability Task Force who asked not to be identified because they are not authorized to speak on the issue, many of the city’s promises on increased oversight, transparency, and rebuilding trust within communities have lagged.

The reason, the task force members say, is due to an apparent drop in federal pressure and employment turnover within the department, including the unexpected departure of Emanuel’s handpicked reform czar, Anne Kirkpatrick, in January.

A clear example is the CPD’s third-party misconduct hotline that would allow police officers to make anonymous complaints within the department. Though the hotline is ready and was supposed to go live on April 3, it is currently awaiting CPD approval, according to former task force member Inspector General Joe Ferguson: “At CPD’s request, we have invested months into creating a completely anonymous hotline. We are waiting for CPD to tell us when they are ready to go live,” he says.

CPD says it’s looking ahead despite the setbacks. “The reforms we have made over the past year are built on the principles of partnership and trust between our residents and our officers, and they laid the foundation for the 2017 reform plan we outlined just a few weeks ago,” says CPD spokesman Anthony Guglielmi. “Reform is in our self-interest and that is why Chicago has been, is, and always will be committed to reform.”

Failures

Since promising to issue quarterly progress reports, the city has failed to update Chicago residents on a number of changes within the department, including those that will be influenced by this summer’s union contract negotiations.

But it’s not just the public that’s been left out of the loop; despite convening the Police Accountability Task Force in 2016, Emanuel hasn’t reconvened the full group since it released its report, according to one unnamed task force member, who is surprised that the mayor did not approach the group to discuss best practices, considering the amount of time and effort put into researching the report.

When it comes to the mayor’s reform promises: “There were a lot of omissions. For example there’s nothing [there] relating to the various collective bargaining agreements, which the mayor continues to be silent on,” task force chair and Chicago Police Board president Lori Lightfoot says.

(Still, Lightfoot says it’s important to look beyond the mayor’s 2016 list to see where the city has made major changes to the police department, including the creation of the Civilian Office of Police Accountability, which passed City Council in October.)

Meanwhile, the Bureau of Internal Affairs, which reviews the majority of police misconduct complaints, “remains a big black box,” Lightfoot adds. “One of the problems is [that] BIA puts out so little information publicly. CPD is going to produce an annual report, but what about BIA? It should be putting out info on a quarterly basis just like [its civilian counterparts] will be doing.”

Also of note, the Trump administration’s decision to ”pull back” on civil rights probes of police departments, including Chicago, decreases the external pressure for CPD to make substantive changes. CPD produced its 2017 roadmap for reform but “it’s unclear what the timelines are and who’s responsible for deliverables,” says the aforementioned task force member who asked not to be identified. Without that “we’ll run into the same problems… We need ownership, as in these are the deliverables and here are the benchmarks we’re going to hit.”

As the other unnamed task force member puts it, the most important failure has been the city’s lack of transparency, which “makes it so difficult for citizens to know where progress is being made.”

This report was produced in collaboration with Chicago Magazine. Additional reporting by Timna Axel and Ryan Cortazar of the Police Accountability Collaborative.