Some have sons in prison. Others have sons who were murdered. At Precious Blood Ministry, this group of mothers sits shoulder to shoulder each month to talk about love, grief, and their toughest challenge as parents: losing a child.

By Sarah Conway. Photos by Sebastián Hidalgo.

I. Mary

Mary Thomas sits in an empty circle of chairs, waiting to talk about Ke’Juan.

A clatter of silverware and bursts of laughter emanate from the room next door, which she just left, where a crowd of mostly middle-aged women hug and kiss while balancing plates of taco salad and cups of coffee. It’s a change from the stillness of Thomas’s home where she has spent most of her time since Ke’Juan’s murder three months back. “It will be different to get out and talk to people today,” she says.

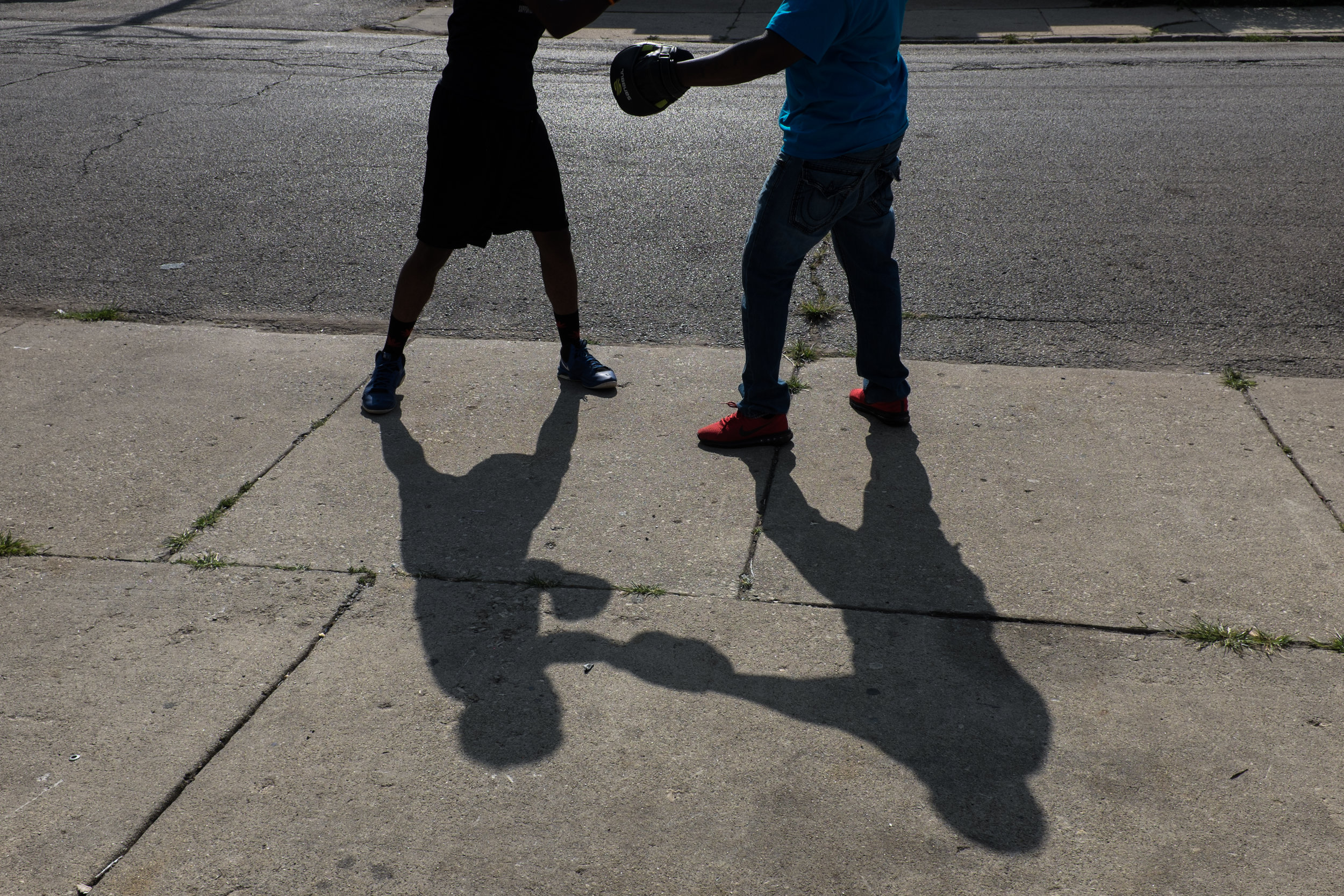

It’s the third Saturday of the month: time for the Mother's Healing Circle, or the Mama’s Circle, as it's known among devoted attendees. Anywhere from 10 to 20 women meet each month at Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation, a tawny brick L-shaped building on a spacious lot just north of Sherman Park. Since its creation in 2013, some 50 women from mostly the Back of the Yards and Englewood neighborhoods have attended this “peace circle,” where mothers who have lost sons to gun violence and the prison system can find peace, sisterhood, and community without judgment.

Holding her phone, Thomas scans through her late son’s Instagram, a patchwork of dance videos and selfies punctuated by laughing smileys and devil emojis, ending abruptly on August 16, 2017. Together, they tell the story of 16-year-old Ke’Juan, who loved drawing and learning new dance moves from YouTube and dreamt of making it to college on a basketball scholarship.

“Come on Ke’Juan, show her how you can dance,” the 40-year-old whispers to her phone, clutching a black sweater around her thin frame as her favorite video loads. She doesn’t go out much these days. Sometimes she feels haunted by Ke’Juan—she’ll feel her bed shake a bit while she's watching TV, as if he is crawling up to cuddle her like he used to.

Outside the window, a gray November sky frames the ministry’s peace garden and labyrinth, a space Thomas’s daughter helped plant a few years back in what was once an empty field near the corner of 52nd and Throop. On Thomas’s phone screen, Ke’Juan appears, adjusting his tall, six-foot-two frame for the camera, then performs a dance routine in his socks on the family’s living room floor.

“Dance, act silly, and play basketball—that’s all my son did,” says Thomas, touching the final still of Ke’Juan on her phone. “He really didn’t deserve it.”

“It” was Ke’Juan’s murder. He died on the Bradley Park basketball court near 97th and Yates in South Deering last August—one out of the 3,457 shooting victims in Chicago in 2017. According to a Tribune report, prosecutors alleged that the shooter walked up to Ke’Juan, pulled out a gun, and shot him in the head. After Ke'Juan fell to the court, the other man stood over him and continued to fire as children as young as 10 years old watched, prosecutors said. Ke’Juan’s older brother was there that day, too.

Farther down his feed, Thomas pauses on a photo of Ke’Juan and his brother, Kenny, deep in laughter, clutching one another in the bathroom after they begged her to relax their hair. “They almost killed their mama with all those chemicals and my asthma,” she says, laughing.

She gets quiet again. “Really, you don’t laugh like you used to. But today isn’t for crying,” she says, wiping fresh tears from her face. Soon after the shooting, Sister Donna Liette, who leads the Mother's Healing Circle, called her to invite her to this special group. It took her three months, but finally, she's here.

II. Donna

The seats around Thomas fill up, and Liette taps a Tibetan chime of compassion three times to make the room fall silent. She lights a vanilla-scented candle to “honor the sacredness of the space.” A Catholic nun for more than six decades, Liette dances the line between New Age spiritualism and traditional religion as the official circle keeper, a skill she picked up 12 years ago.

The peace circle is a cornerstone of restorative justice, a mediation philosophy that brings victims and perpetrators together to repair the harm that’s been done to all parties and strengthen the community. Restorative justice has steadily gained steam in Chicago since its induction into public schools in the mid 2000s; it made a big institutional leap when the Restorative Justice Community Court in North Lawndale opened last August. The Mama’s Circle, according to Precious Blood staff, is the only circle in Chicago that brings together mothers of sons who have committed and been victims of crime.

Since spring of 2013, women have gathered here to coo and cackle, tell jokes, knit, and sip coffee. Some mothers cry and yell in small outbursts of anger, recounting bad former husbands or the young men who put out their sons’ lives. Almost all have suffered from the lasting trauma of gun violence—either losing a child to the prison system or the grave, and if not a son then a nephew, a brother, a cousin, a spouse, a father.

At 78, Liette has a small frame, a dandelion puff of white and black hair, and boundless Midwestern energy. She spent more than five decades in ministry and faith-based teaching in Ohio. “I was almost 70 and Father Dave Kelly [of Precious Blood] called me and said, ‘We need you in Chicago.’ I said, ‘Oh, I’m too old now to go to Chicago.’”

But Kelly’s offer was persuasive: Liette was drawn to how the ministry uses restorative justice to help people in the prison system, and she appreciated its holistic approach to combating violence by investing in community relationships. So she prayed on it, and the Friday after Thanksgiving eight years ago, she packed her car for Chicago.

It was in her first role visiting (or “journeying,” as she calls it) with young people in detention centers that she realized that mothers were too often left out of the healing process. “I kept hearing [from the kids], ‘Please call my mother.’ ‘I wish I was with my mother.’ Over and over I heard the words, ‘my mother, my mother,’” Liette says. So, she thought, “Why don’t we honor the mothers that are often left behind to deal with the trauma and pain of losing a child to prison or gun violence?”

Today’s circle starts with announcements. The holidays are coming, so find quiet time for yourself, she reminds the crowd. Stress management meetups are still on Wednesdays. (They’re discontinued now.) “Quite a few of you are getting jobs and that’s exciting!” she exclaims to the applause of the 20 or so women in attendance.

Liette runs through the circle rules: Always speak your truth, even though your truth might be different from someone else’s. Respect each other and the stories. Listen with our heart. And, last but most important, whatever is said in circle stays in circle. (That’s why, besides Liette and Thomas, who agreed to be quoted, none of the quotes during the circle are attributed to named individuals.) Several mothers nod in silent agreement, and others yell out, “Amen.”

A “talking piece” is passed around the circle, and each mother introduces herself and shares one reason she came. For some, it’s for peace of mind; others, to see everybody in a space where they won’t be judged. Then the piece reaches Thomas, the newcomer.

“My name is Mary. I came here cause Sister Donna asked me to,” she starts.

“You’re welcome here, Mary,” shouts out one mom.

“I came to listen and to take this one day at a time. My son got killed August 16,” says Thomas, beginning to cry. The circle sounds off with sighs. They have been there before. Mothers new to the circle almost never make it through their first time without breaking down.

“Oh, baby, can I give you a hug?”

Thomas nods as a mother rushes to her and holds her. “We’re gonna come together now and I’m going to keep you strong,” she tells Thomas. “I don’t feel strong every day but we are coming together and talking about it. We are going to get strength and strength and strength!”

The energy of the group flares up again and the talking piece is passed on; other mothers talk about the stress of the holidays, but many glance back at Mary, trying to draw her into their space.

“How old was your son, Mary?”

“Just 16.”

“Oh, baby, that’s too much.”

III. Sakena

At first, the circle was a failure. For the first meeting, two or three mothers came. The next month it was one. Then, none. But Liette and Sara Nuñez, a volunteer at Precious Blood, continued to organize the monthly meetup, and eventually the group took off, slowly building its way to around 20 mothers attending a brunch, then a circle, with Liette’s staples of “casseroles and coffee, china and silverware.” Today it is one of Precious Blood Ministry’s most recognized programs, where mothers say they can share their “tears and fears.”

“Oh, Sister Donna, she’s crazy!” says Sakena Barnes, 41, with a chuckle. She has attended circle for the past four and a half years since its creation. “At first, I was like, I don’t want no peace circle. But I’ve been coming ever since.” It's the anonymity and intimacy of circle that draws her—and the lack of access to pricey therapy sessions.

“We can say whatever we want to say, we can cry, we can laugh, we do it all in there,” says Barnes, who says she gets stressed about her 21-year-old son’s fear of getting shot. “My baby don’t even come outside. He won’t even walk to the store by himself,” she says.

Today she is something akin to a circle recruiter; she calls women or knocks on doors to expand the group’s membership. “We want to show mothers that we care. If we could get 1,000 moms up in there, that’d be great, but you can’t force them to come,” says Barnes. But once a mother does show up, she is usually hooked.

“All the mothers in there, we are a family, we are a community. If someone’s child gets shot, it hurts all of us. If someone’s child gets thrown in jail, it hurts all of us,” she says. “We have lost a lot of our children in the past year. We talk in circle, but then we talk at home, too. We text every morning: ‘How you doing?’ We call: ‘You all right?’ When you’re at home and you are stressed and crying alone, we will calm them down and talk to them.”

Barnes says a lot of the moms blame themselves for whatever happened to their sons. While the circle can’t be the solution to all their problems, it’s a place where they can feel valued—“for just being a mother, period,” says Barnes.

As one mother says at the November circle, “Time is one of the biggest healers. A lot of people want things to go back to normal after your son dies, but it doesn’t ever go away. Healing doesn’t get easier, you just learn to cope with it.”

IV. Julie

For the past 22 years, Anderson says she feels she’s lived the old adage: “good parents, bad kid.” Over coffee just outside her office at Precious Blood Ministry, she recounts how her son Eric was convicted of killing two 13-year-old girls, Carrie Hovel and Helena Martin, in a 1995 shooting, when he was just 15. He was sentenced to life without parole. People don’t understand it: the slow death that a mother of an incarcerated son feels, each time a visit ends and she sees her baby return to his cell, she explains. Watching her son disappear into the criminal justice system has been deeply isolating. “Some of it isn’t just people judging you as a mom. It is that they judge your kid,” she says.

Over the years, the Andersons have never missed a visitation opportunity—five per month for 22 years, adding up to more than 1,300 visits, sometimes traveling over 100 miles each way. Though she recognizes the terrible harm Eric caused, she says she deeply loves her son and believes he has atoned.

Eric, now 38, has spent more than half his life in prison. But in 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that mandatory life sentences for minors were unconstitutional, so he was resentenced and now has about eight years left to serve. At the time, Eric was one of nearly 100 people in Illinois serving life without parole for crimes they committed as minors.

“Seven and half more still feels really far. I will be almost 70,” says Anderson, who is 60. “That’s old. I have to make it … I’m always telling Father Kelly, I just don’t want the bitterness to take over my heart.”

Anderson has long felt the tension of existing in two worlds: She’s married to a former Chicago police officer and has lived a life of white, middle-class privilege—the type of life where people tend to be unfamiliar with the criminal justice system. “When I sit with my friends, I might as well be talking about the moon” when she explains the injustices of overcriminalization and mass incarceration, she says. “They think Eric should get out, definitely, but nobody else. He has a good family, a place to go, but the rest of these guys, no.”

Yet she’s also a Precious Blood-based organizer and the founder and coordinator of Communities and Relatives of Illinois Incarcerated Children, where she fiercely advocates to improve the conditions of children in the adult criminal justice system. As part of her job, she visits incarcerated men serving life sentences so they can have a visitor and just a normal conversation. “We never talk about their case and what they did. It’s always ‘Hey, let me buy you a pop and a vending machine hamburger, and we can sit and talk about the Cubs,’” says Anderson.

Anderson remembers searching for a support group for mothers in a similar situation to her a decade or so back. “I couldn’t find anything that said, ‘Hey, your kid did a really horrible thing but we are going to help you and support you anyway.’ The concept didn’t even exist until I found the Mother's Healing Circle,” she says.

Today, the circle has become her “free therapy,” but it didn’t always feel this way. When she first joined, she says she felt like a nuclear bomb among mothers whose sons committed lesser crimes—she was the only one whose son was locked up forever.

Even in this group, she felt alone.

Then Timika Rutledge-German walked in.

V. Timika

“I don’t know why I’m even here. I lost my son to gun violence,” Rutledge-German remembers saying when she got the talking piece at her very first meeting. Two and a half years after Liette convened the group, the nun had delicately opened it to mothers who had lost children to violence, as a way to encourage reconciliation and healing. Rutledge-German was the first.

She, like Anderson, didn’t think the circle could help her. Her 15-year-old son, Cornelius German, was murdered on April 22, 2013, just blocks from Barack Obama’s Kenwood home. She remembers saying to the group, “Your son is in juvenile [detention] but mine’s never coming back. I have to go to the grave to see him.”

Then she heard Anderson speak about Eric serving a life sentence, and something about the other woman’s loss felt familiar. The two immediately connected.

Inside the Sister Brenner House at Precious Blood one November morning, Rutledge-German, 46, describes her son: “I called him Bread, short for Cornbread.” She’s quick to admit he wasn’t the perfect kid—he hung out with older friends, some who are now in prison, others who are dead—but he was her angel. “He had character and spunk. He was like cornbread that you put in syrup—he just sucked up everybody and everything in a space,” she says.

Funny and short, with his mother’s lips, Cornbread had a ferocious appetite, a characteristic that Timika honors with a birthday party every November 17 with family and a few of his friends who still send her heart emojis when they text her to check in.

“Cornbread eat,” says Rutledge-German with a laugh, shaking her head. She serves up the works for his “birthday Thanksgiving” celebration: pasta with alfredo sauce, dressing, greens, deviled eggs, ham, turkey, pies, and always, always, tall glasses of strawberry Kool-Aid, his drink of choice.

Toward the end of his freshman year at Kenwood Academy, Cornbread was shot walking out to the gate toward his mother’s car. “Even though, he wasn’t the target, he was the victim,” says Rutledge-German. “His friend told me that his last words were, ‘Call my mama,’ and all I could think of was, your mama was right around the corner… It was just him and the sky, laid out on the grass, waiting for his mama to arrive.”

Trying to make sense of his murder, Rutledge-German says his death delivered her to Precious Blood’s circle. At first, she struggled to explain to the other women what her loss felt like: There would be no more birthday Thanksgivings, no homecomings, no marriage or grandchildren. But her words resonated with Anderson. It was a moment of healing for the two mothers struggling to accept the loss of their sons.

Rutledge-German’s story was the first time she felt connected to the group, Anderson says. So many mothers carry their guilt in private. “It’s that fear of being judged—but those moms in that circle, they don’t judge people,” she adds. “We are all healing each other in different ways.”

“Now, some of us vent longer than others,” Rutledge-German says, jokingly. “We’re like, Your time is up! Pass the talking piece on. We got something to say, too.” But in all seriousness, she adds, it’s a place where the forgotten mothers behind sensational headlines can love one another. She and Anderson are something of a symbol for what the group has become: a place that brings together mothers on the opposite ends of Chicago’s violence.

“We are hugging and kissing because we really miss each other,” Rutledge-German says. “That’s so exciting to me ’cause I don’t have any friends, and to be able to come to that circle and be able to smile, and grieve”—she takes a deep sigh, closing her eyes—“I’m not going to say I’m at peace now with Cornbread’s death, but I feel differently than a lot of people about their grieving process because of that circle.”

“That’s what this group does. They help my heart.”

VI. Mary, again

Thomas can't honestly say she’s at the point to forgive her son’s killer. She's just trying to stay busy. “I shine the table three times. I clean the house seven times a day,” she tells the circle. Some mothers nod their heads, seeing their own trauma reflected back at them.

“I can’t say nothing bad about Ke’Juan. None of my children. That’s why I was so blessed to have him,” Thomas says.

“How many you have now?”

“I have three now.”

“Naw, you have four. He is always going to be with you spiritually,” says one mother. Thomas smiles for the first time.

Before long, it’s time to wrap up. Liette announces that there’s more coffee and sweets in the brunch room before she asks each mother to share just one thing for which she is grateful.

When the talking piece makes its way to Thomas, she thanks Liette for the invitation. Her voice is now steady and strong. The mothers clap and hug her as the circle ends. While some tuck themselves into winter jackets to brave the chill outside, Thomas lingers to grab a bite with the dozen or so women who remain.

Will circle help?

“I don’t think anyone in their right mind can get used to their child being gone,” she says, reflecting on the question a few months later. The experience has given her cautious hope, and she feels less alone when she’s shoulder-to-shoulder with other mothers facing the same pain. Still, she says, "I just don't know how I'm going to heal.”

Thomas missed the next two Mother's Healing Circle meetings. She is still acclimating to her post-August 16 life, with its few ups and its deep downs. In January, she and her kids moved to a safer neighborhood; community members who heard about what happened banded together to help her find the new place. But she'd quickly give it up to bring her son back.

“Ke’Juan always promised me a home, and in the end he got me one,” Thomas says, recalling how her son would talk about making enough money to alleviate the family’s housing woes. “I just wish he was there to be in this house with me.”

Instead, she’s found a quiet corner in the basement where she plans to keep a few pieces of Ke’Juan’s clothing and photos spanning the stretch of his short life, from chubby-cheeked baby to distinguished student. That’s where she’ll go to light candles, pray, and feel close to him again. Like many of Precious Blood Ministry’s mothers, she’s learning the boundaries of her grief.

Still, she says she'll return to circle, eventually. And when she does, she'll bring more stories of Ke'Juan, his shoeless dancing, and his basketball dreams.

This report was produced in partnership with Chicago Magazine.