Changosnakedog uses puppets, music and multiple languages to connect people across languages and generations. Founder Otto Anzures Dadda speaks on the group’s mission.

By Zulema Luz Herrera

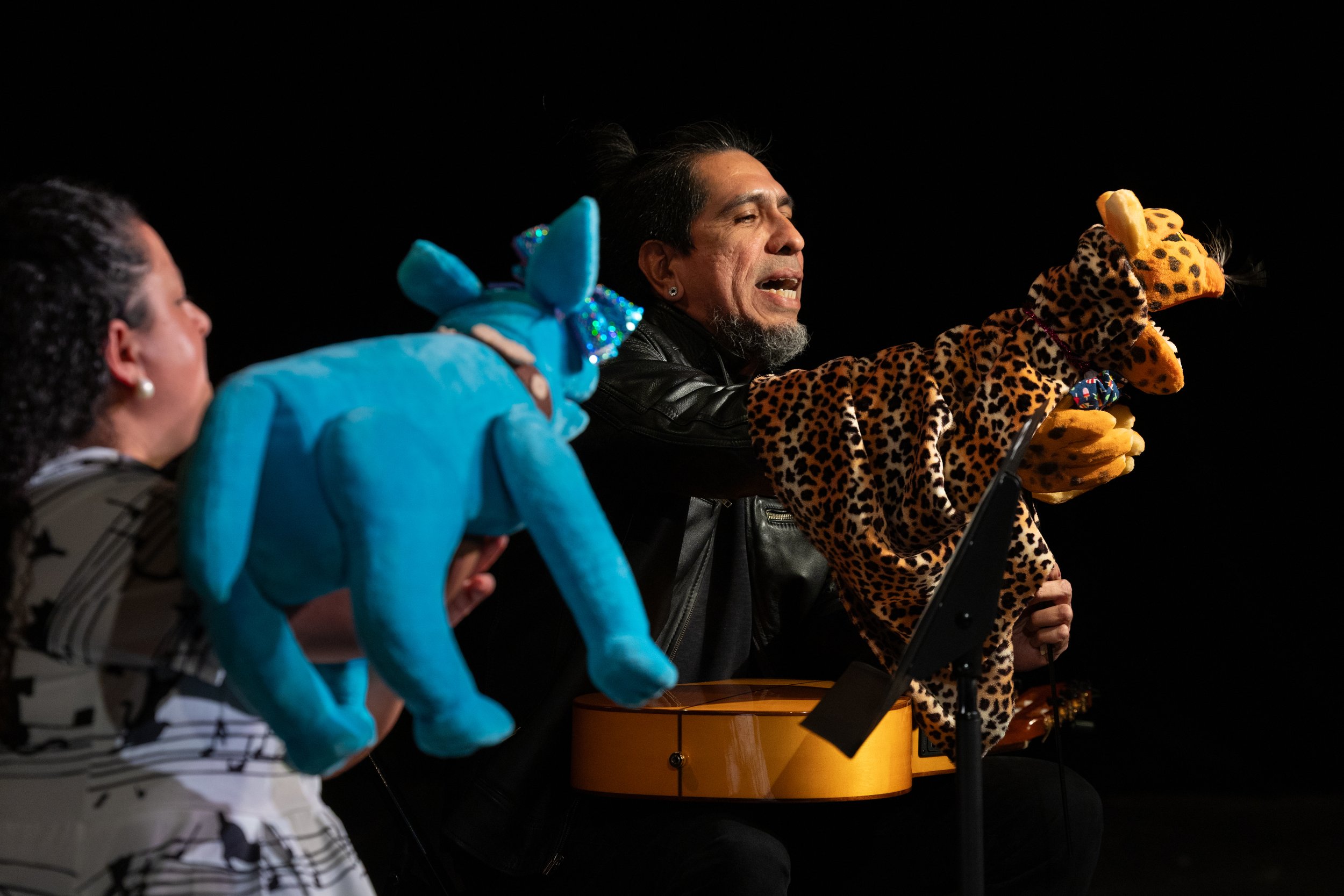

Carolina Gomez , left, and Otto Anzures Dadda of Changosnakedog perform during “Ratas en Fuego” at Urban Theatre Company in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood on Saturday, Nov. 22, 2025. (Heidi Zeiger for City Bureau)

Otto Anzures Dadda began his musical journey in his native Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, Mexico, near Guatemala. Of Xochimilca and Otomí descent, he learned about his heritage through oral storytelling. Though his family did not pass down their Indigenous languages to Anzures Dadda, he feels pride in his roots, honoring it through his art.

When Anzures Dadda moved to Chicago in 2020, he aimed to bring this history and heritage to new audiences with his family-friendly puppet band Changosnakedog.

Changosnakedog performs in English, Spanish and Mayan, and combines musical influences such as cumbia, swing-jazz, reggae, son jarocho and traditional Mayan. They perform live and are broadening their online presence via social media, music videos and a radio show on the Lumpen radio channel.

The puppets include Changosnakedog, a puppy voiced by Carolina Gomez; Zana la Rana, a frog performed by Melannie Gonzales; and Balam the jaguar played by Anzures Dadda.

Through their work, Anzures Dadda hopes to teach people about his culture, create a fun show for all ages to enjoy, and help people reconnect to their Latino heritage and their native languages.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Carolina Gomez, left, and Otto Anzures Dadda of Changosnakedog perform during “Ratas en Fuego” at Urban Theatre Company in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood on Saturday, Nov. 22, 2025. (Heidi Zeiger for City Bureau)

Can you share your background and how you got into the arts?

My granddad used to live with us in my parents’ house. There was always a guitar at home because my granddad played the guitar and the mandolin.

Once he passed away, I started grabbing the instruments like, “Oh what is this thing?” I was 14 or 15 years old — kind of old for starting to learn music.

When I was 19, I decided to formally study music education at school. I learned pedagogy, techniques for teaching children and working with different populations of children. People who go to school there play two instruments: We have the traditional (Chiapaneco national) instrument, the marimba, and … one other instrument.

What inspired Changosnakedog?

We adopted a dog named Itzamara, which means goddess of the stars. We started looking at every single detail of Itzamara, how she moved and how she was sneaking around, moving between chairs like a snake with her long body.

Her mom didn’t like her when she was young; she didn’t have the opportunity to breastfeed. So what she would do is grab a blanket, like a chango (monkey), with her paws opening and closing around the blanket, gathering the blanket in her paws, and would “feed” from the blanket. So I composed a song based on what she did.

I naturally started creating her story. The story is that she came from outer space, and she came here to take care of us, even though we’re taking care of her because she is so young. And then I started adding more characters. The jaguar is basically my story because he comes from Chiapas.

What are your target audiences?

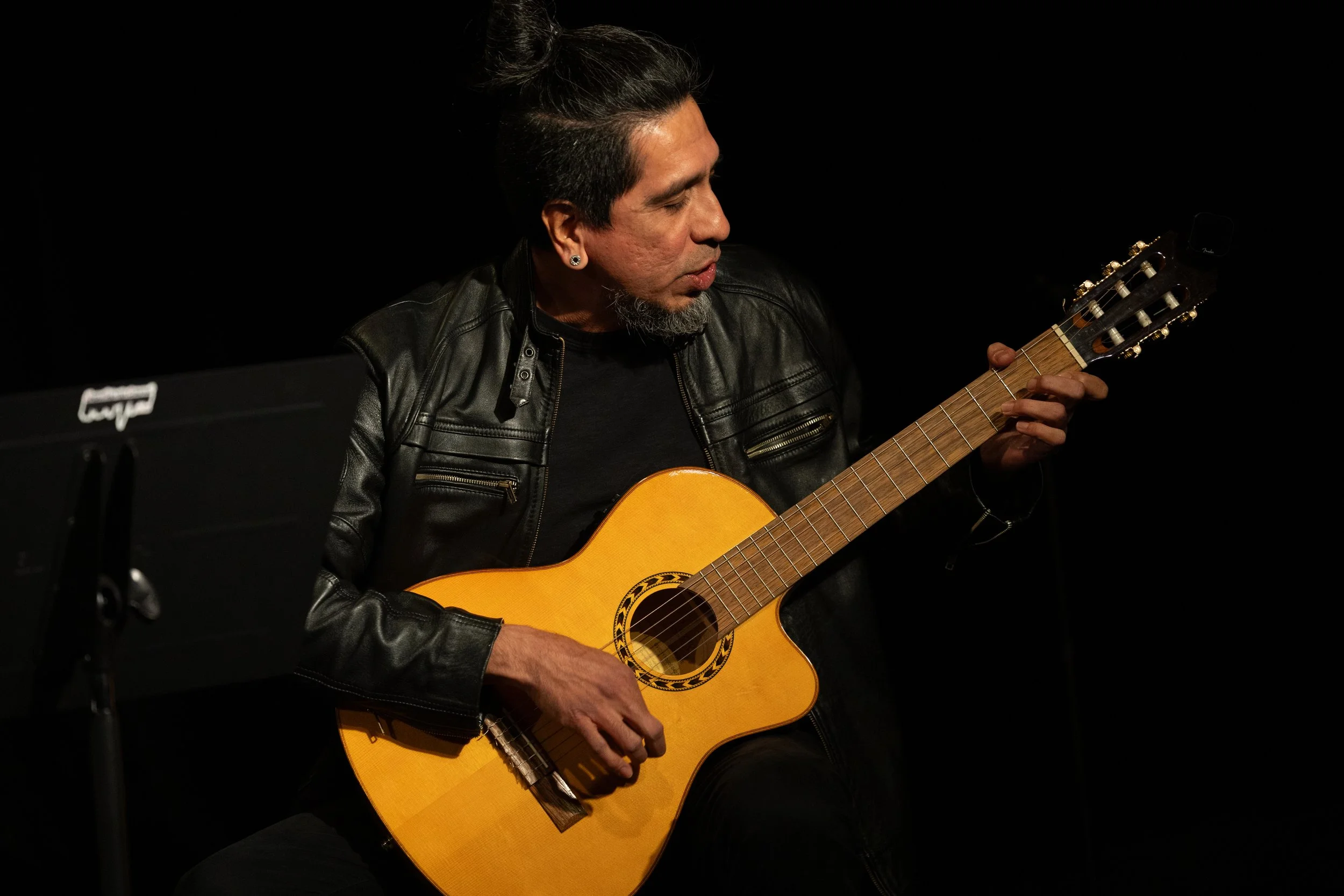

Otto Anzures Dadda. (Heidi Zeiger for City Bureau)

Definitely the younger generations — but that's a tricky thing. You cannot just target one thing, because the family is not just one person, or the society is not just one person, not the country is not just one kind of people.

With our easy lyrics, catchy melodies, nice rhythms, interesting rhythms and amazing musicians playing live, we want the parents to say, “Oh, I can stay here for one more hour,” or “I don't care if those are children's songs,” because they are not really children's songs, just a family-friendly song. They’re made with the intention for everybody to listen and like them. Everybody can understand the message.

You incorporate genres such as cumbia, son jarocho and traditional Mayan, and different languages. Why did you decide to do this?

In Mexico, people from communities with languages other than Spanish move and try to forget their language because of the racism they experience. It’s kind of the same thing now, wanting to protect your children because you don’t want friends to realize that they have a different ethnic background.

People move here without so many tools; people move here without education. I want to try to enrich the community where I am living now. I started composing in Spanish and English and Tzotzil (spoken in the southern part of North America, in Chiapas, Mexico) because I haven’t yet learned the original language of Illinois.

People often associate a Mexican band with mariachi. But we are rockers; we are cumbiacheros.

Changosnakedog characters allude to immigration — one doesn’t have an ID, another is from outer space. What was your motivation for that?

We narrate little stories so everybody can hear that the characters are from different places.

In the last show, I stated at the beginning that I want to share that we are all immigrants. Some of them are like me, who just came to the United States, or they are like Melannie with parents who are immigrants. Some of them, like white people, have grandparents or great-grandparents who are immigrants. And I told them that I am actually half Native American, so in some ways I am not an immigrant, even though I am from Mexico. I joke with the audience that I am the only one that is not an immigrant.

We are trying to break the intergenerational barrier and the bilingual barrier. We also want the children who speak Spanish and English to hang out with the children who only speak English, and also with the children who only speak Spanish. It’s important for the people that speak English to understand other heritages. I think our next goal is to play in more so-called white spaces on the North Side because we want them to understand that our message is for everyone.

Zulema Luz Herrera is a Chicana journalist and musician from Chicago. A third-generation Mexican American, Herrera has journalism degrees from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and University of Arizona, where she produced a documentary on food insecurity in Tuscon and created visual media for a local immigrant services organization. She is part of City Bureau’s fall 2025 Civic Reporting Fellowship cohort.

Support City Bureau’s Civic Reporting fellowship by becoming a recurring donor.